Woven Wind is a multi-layered research project drawing from artistic translations of the Lovell Quitman archive, which includes extensive Quitman Plantation records and photographs of the Civil War era. In a time of social and racial reckoning and division in the U.S., Woven Wind constructs an artistic platform for education, conversation, empathy, and healing. Its artistic team includes artists Vesna Pavlović, Courtney Adair Johnson, Marlos E’van, community advocate Mélisande Short-Colomb, musician/artist Rod McGaha, genealogist Jan Hillegas, and historian Woody Register, director of the Roberson Project on Slavery, Race and Reconciliation at the University of the South. Archival research studio and field work, community engagement, genealogical findings, and conversations with the descendants inform the project.

Thank you Toles Family for allowing us to listen and welcoming us to your family.

Woven Wind is supported by Tennessee Arts Commission Arts Access Grant, Vanderbilt University Scaling Success Grant, Mellon Partners for Humanities Education Collaboration Grant, Vanderbilt University, Engine for Art, Democracy, and Justice, Tennessee State University, Curb Center for Art, Enterprise and Public Policy Catalyst Grant, the Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation at the University of the South, Sewanee, and Natchez Museum of African American History and Culture.

Cotton and Cypress Knees

written by Dr. Shelley MacLaren The University of the South, Sewanee, TN.

The collaborative project Woven Wind brings together many voices and methods, and multiple ways of thinking (1).

It deploys photography and video, sculptural installation (sometimes site-specific and sometimes not), music, genealogical research, oral histories, storytelling, and ceramics workshops to activate archival materials, to make them strange, and to read past them. It does so in order that we might remember together, and work towards community and healing in the present.

Beginning as a critical archival investigation and experiment in one place, Woven Wind has changed and grown over time, and it will continue to do so. Now an exhibition, it will most certainly shift in meaning as it moves to different sites and engages other audiences. It will bear different responsibilities each time. It is expansive.

Two metaphors bookend the project. The title, Woven Wind, refers to fine cotton (2). The other is cypress knees, knobby protrusions that emerge from the trees’ roots, represented in the exhibition in abstracted clay objects and photographs. The one feels light, insubstantial, amorphous, fleeting, whispering, and the other heavy, grounded, still, tactile, and silent.

Both metaphors speak to entanglements and connections. Both are useful for thinking about this project, and both are inadequate on their own. They don’t sit comfortably together. The difficulty speaks to the project. It tells us that no metaphor is adequate—that no metaphor can be —and that they might change, that other metaphors and forms of expression might come to the fore as the project evolves.

In its original use, “woven wind” described cotton, a commodity inseparable from global commercial networks and the institution of slavery. This project takes that phrase and remakes its meaning. It no longer describes a commodity or bounded object, but many voices—threads—brought together in conversation.

The appropriation and reinterpretation of the metaphor—from cotton to combined voices—is emblematic of the work that began the project in 2018, that of making use of archival materials to tell new stories, and even—in the words of Dr. Woody Register—to “desecrate” or to treat those materials “irreverently,” that is, to use them in ways counter to the purposes for which they were first collected and safeguarded (3).

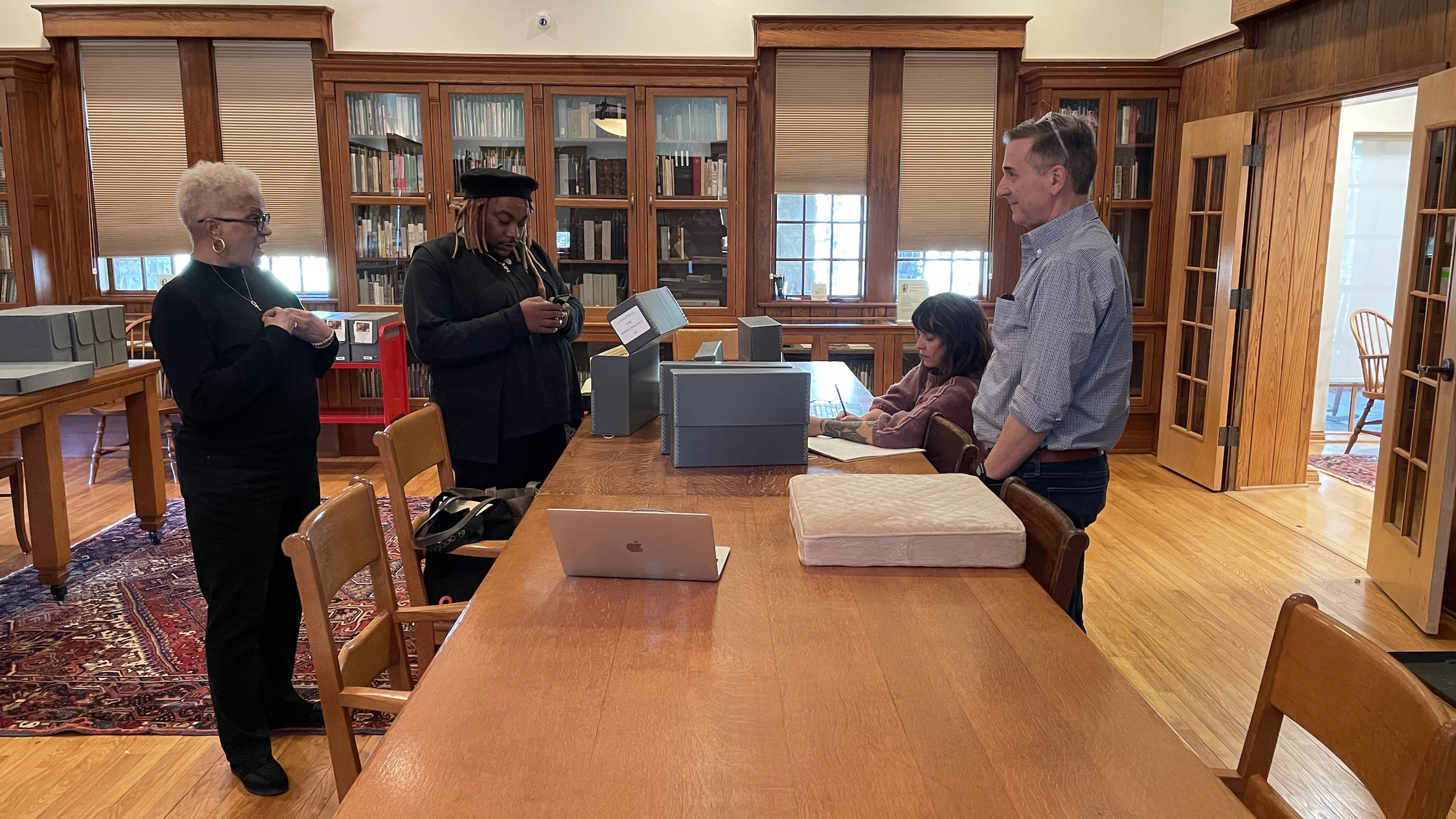

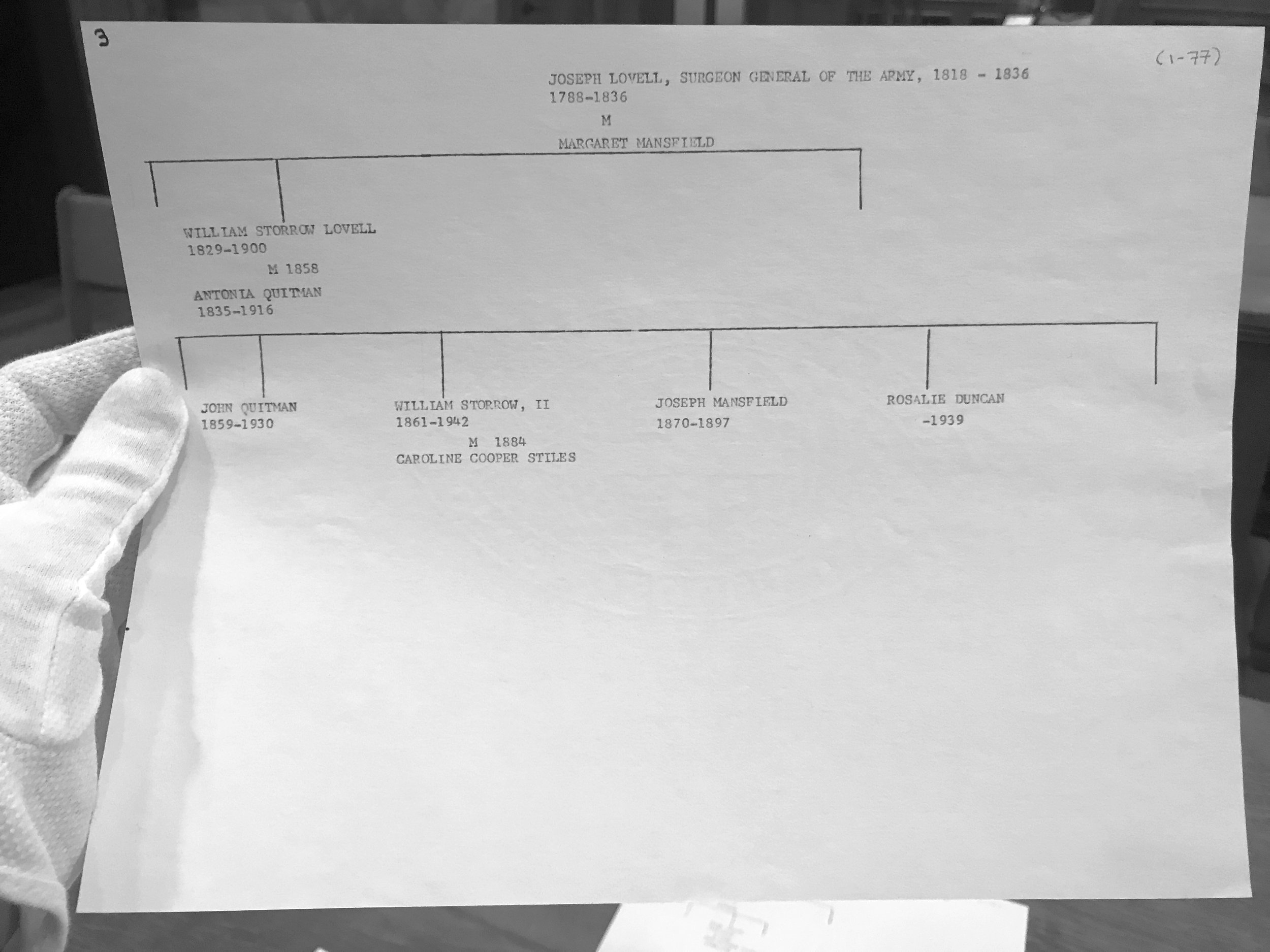

I introduced Vesna Pavlović to Dr. Woody Register, Director of the Roberson Project of Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation in 2018. Both photographer and historian were engaged in thinking about the ways institutional archives reify and perform power, in thinking about how to tell different stories with archival materials, and in thinking about how to bring archival materials to life. With that meeting, Vesna joined the investigation and presentation of the Lovell Family archive undertaken by Woody and his students in History 328: Slavery, Race and the University, a class considering the methodological question of how to tell the story of the university so as to confront slavery and its legacies.

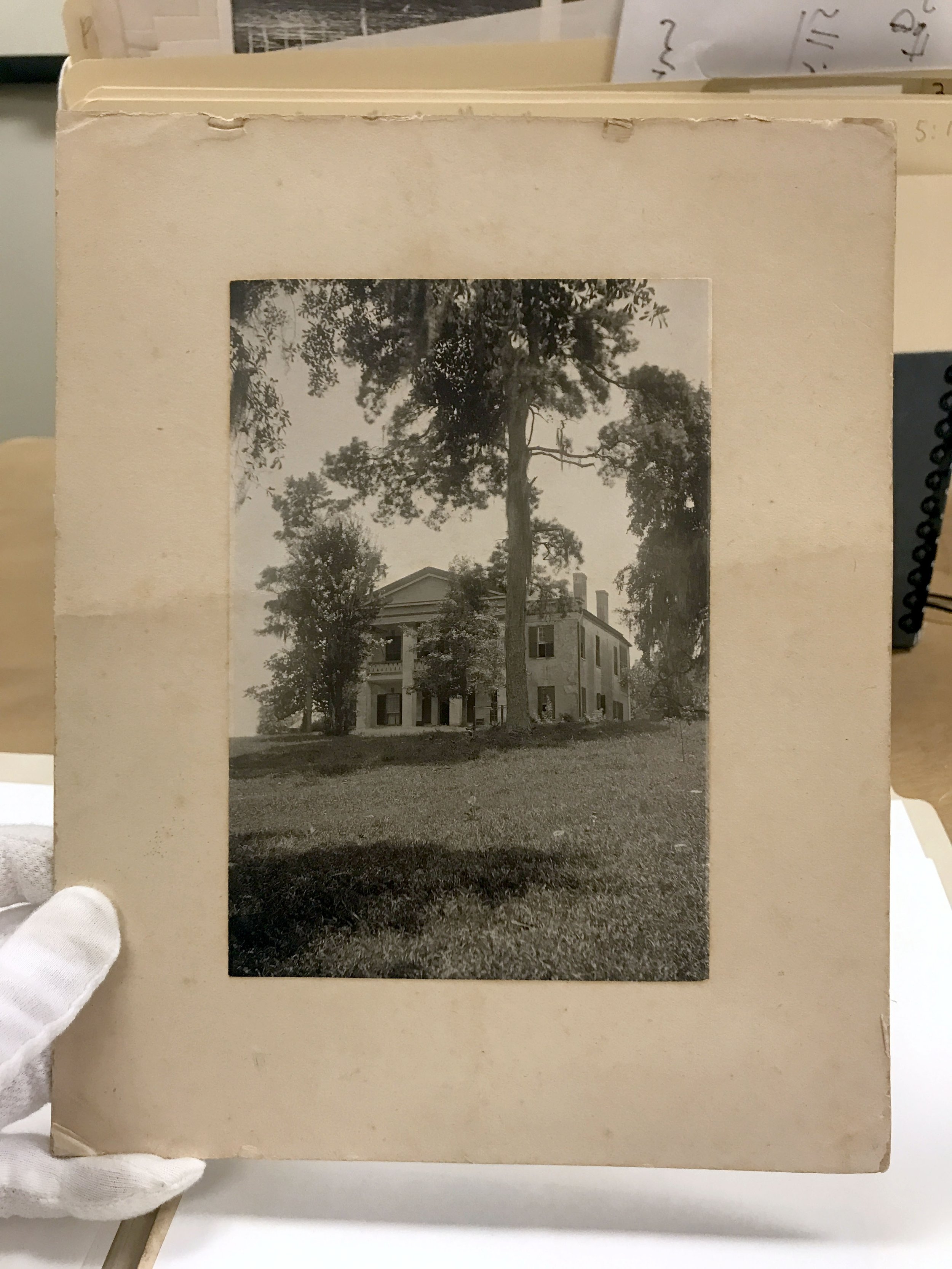

The Lovell Family archive offers a lot to think about in relation to Sewanee. William S. Lovell bought a home called Sunnyside in Sewanee in 1873, and the family was part of the community for 65 years. Hunter Hall dormitory, close to the heart of campus, now occupies Sunnyside’s site.

William S. Lovell was married to Antonia Quitman, daughter of General John A. Quitman, governor of Mississippi (1835-36 and 1849-51), and planter. The three Lovell sons—William Storrow Jr., Joseph Mansfield, and John Quitman—attended the Sewanee Grammar school and the university, and were important in collegiate life—playing baseball and founding the Omega chapter of the ATO fraternity on campus, the first fraternity in Sewanee. The family donated money for the Rosalie Quitman Duncan Lovell and the Antonia Quitman Lovell Scholarships. Rose Duncan Lovell, one of William and Antonia’s daughters, was an editor of Purple Sewanee, a collection of vignettes about life in Sewanee, first published in 1932 (4). Rose’s death in 1939 brought the remaining Lovell Family papers to the custody of the University of the South.

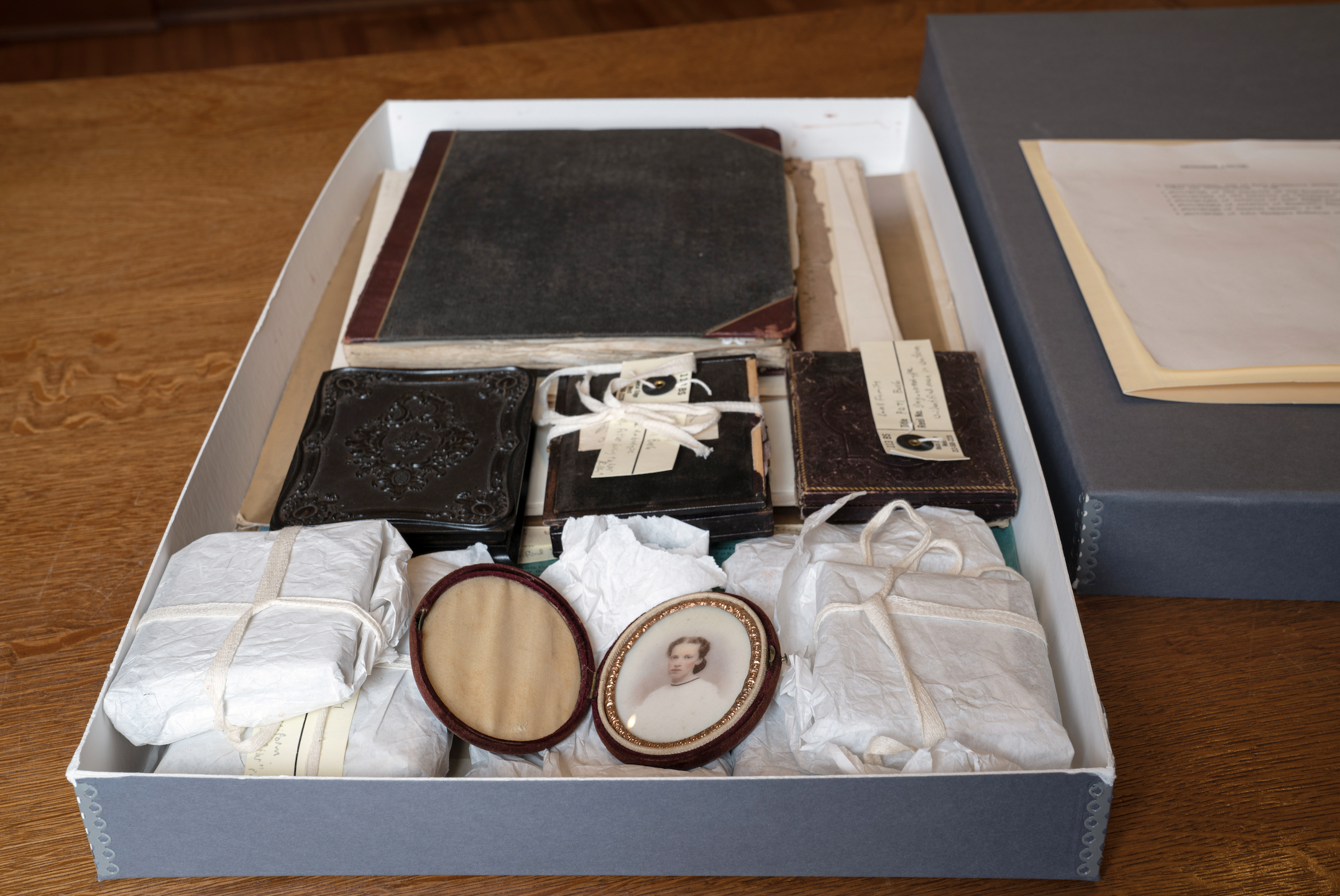

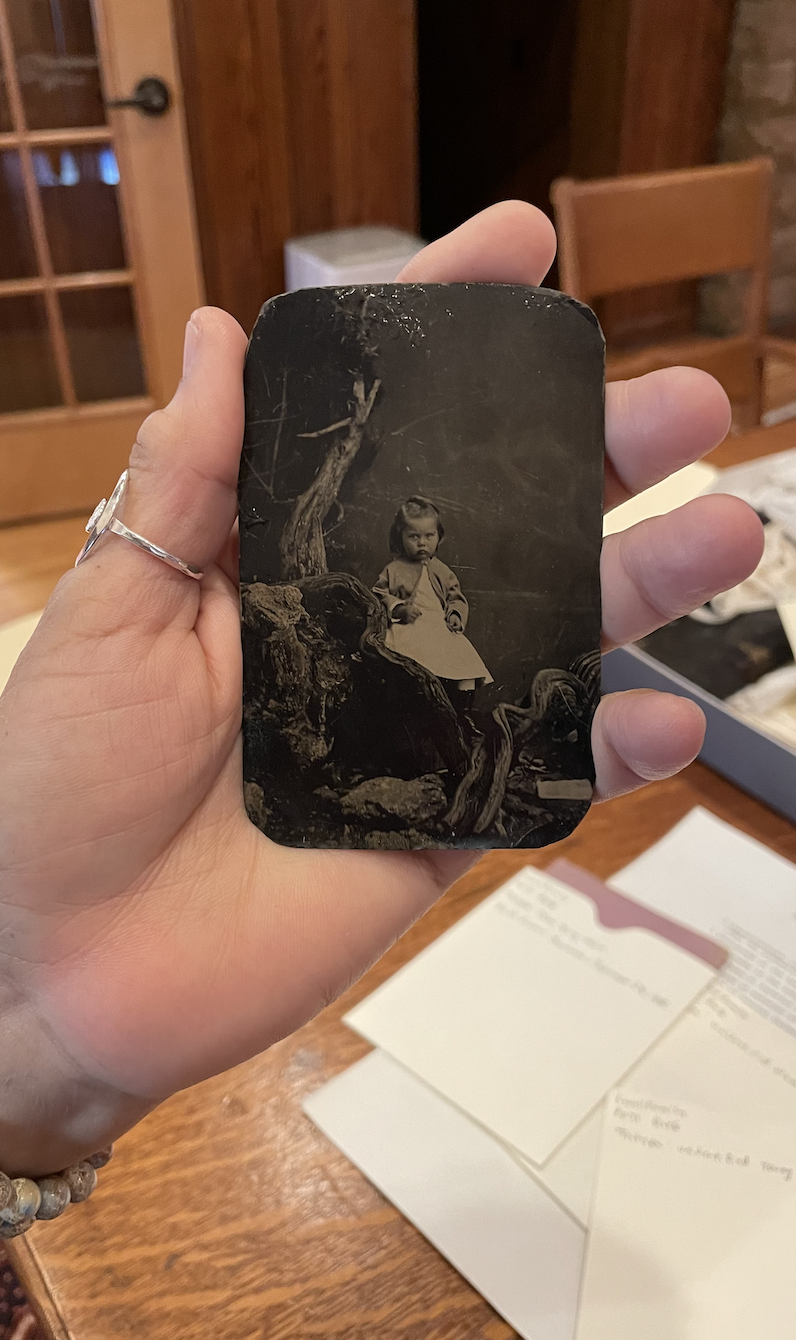

Looking through the boxes, one is struck by the abundance of documentation and description (5). There are biographies, diaries, and newspaper clippings. There are ambrotypes, daguerreotypes, engravings, and photographs of the Lovells reclining in their garden in Sewanee, or in conversation with one another in their Sewanee home. There are postcards of Natchez and the Lovell plantation home Monmouth, celebrating—and mourning—the antebellum Old South. There are maps of plantation boundaries, there are mementos from Confederate reunions, and there are amnesty oaths signed by members of the family following the Civil War. The few African Americans represented in pictures in the archive - on postcards - are not given specific identities, but are instead used as types, labeled as “Mammy” and “Uncle Tom.”

As this list shows, these carefully kept materials dictate to us. It’s hard not to get lost in describing them. We know what the Lovell family members looked like. We know where they lived, what they wore, and where they traveled. We know the boundaries of their land. The archive represents the privilege, and ideology, of those who kept and collected the materials. Even to describe these materials feels risky, a reiteration of privilege, an invitation to misdirected curiosity.

In 1921, Sarah Barnwell Elliott, author and daughter of Bishop Stephen Elliott, a founder of the University of the South, wrote An Appeal for Southern Books and Relics for the Library of the University of the South (6). She described the Confederate bonafides of the founders, and wrote, “thus the University of the South at Sewanee is the fit Representative-the Child and Heir of the Old South, worthy to be the Custodian and the Conservator of all Southern Relics … to be kept here Safe and Sacred. Gather them, … send us those relics of our beloved Country, so that the future historian can here read and study the truth about us.” Her appeal identified the University of the South with the Lost Cause, and sought archival material that would calcify that identification and legacy. The Lovell family’s archival materials are just such relics (7).

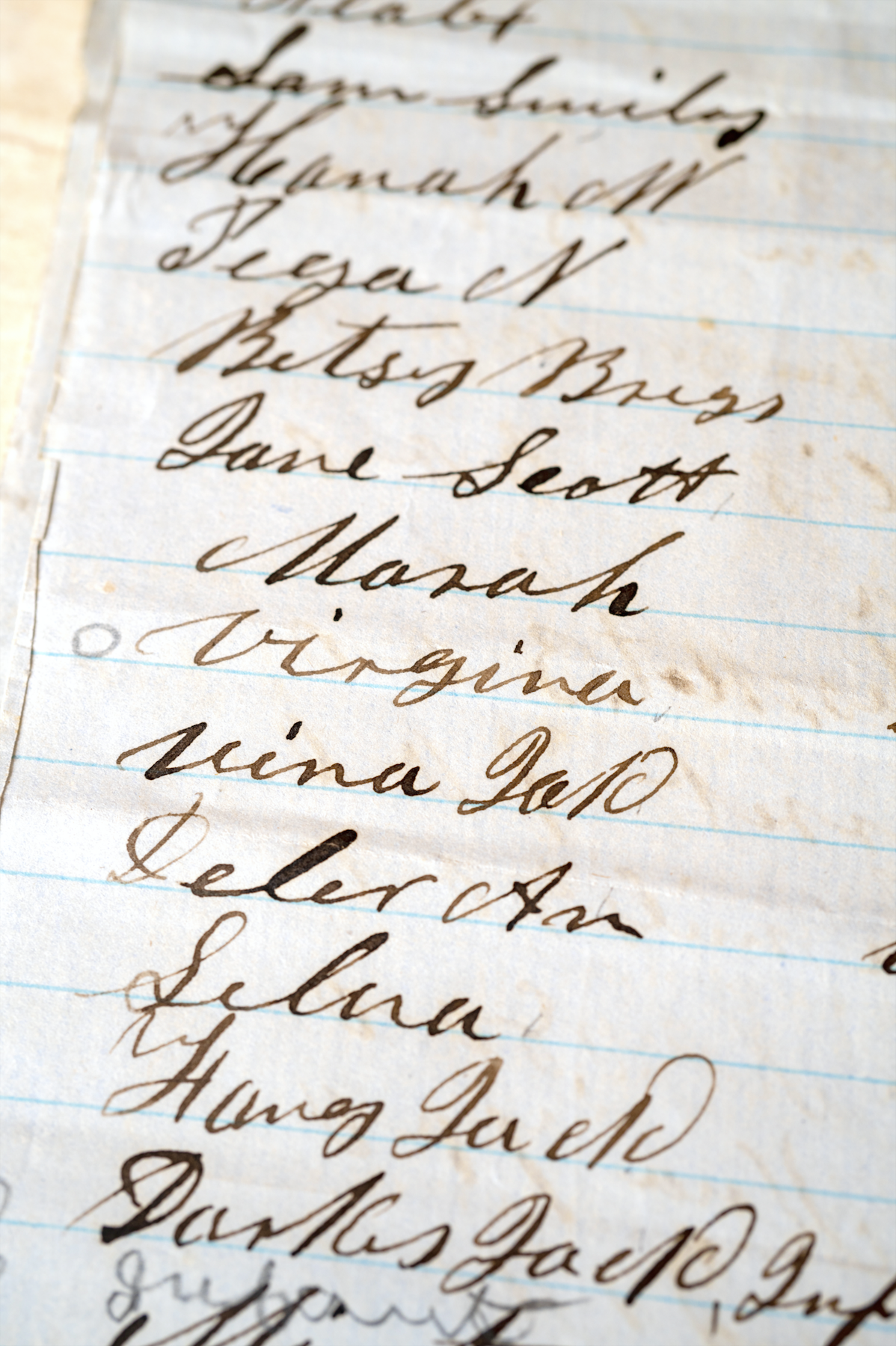

Most painfully, among the Lovell papers is an inventory, produced as part of the documentation of the estate of John A. Quitman after his death in 1858, listing the names, ages and assessed values of the hundreds of enslaved persons held on Quitman’s plantations. In marked contrast to the abundance of description of the Quitman-Lovells and their lives, all we know of these people and their stories are names and ages.

Desacralizing the Lovell Family archive—working counter to its methods and purposes, finding stories and voices beyond those represented—is imperative. The effort to do so raises many questions. How does one remember and honor the enslaved, without repeating the objectification to which they were subject, and without rehearsing and repeating that violence? How does one use archival materials without simply repeating the privileged position through which they were assembled? How does one do so so as not to serve only one’s own purposes, or institutional purposes, but, somehow, someone else’s, or everyone’s? How do you approach critical archival work in such a way as to build new relationships, future communities, to open spaces for healing and storytelling? To answer any of these questions requires care, and answers can only be offered tentatively, and with humility.

Woven Wind’s insistence on metaphors, on making and unmaking them, and on gathering other voices and perspectives as it does so, works to all of these ends.

The first performance of what was to become the Woven Wind project took place on October 14, 2018, with a Community Screening performed in the University of the South’s Convocation Hall. Materials selected from the archive were projected throughout the space, and students interpreted the materials for community members. Most powerfully, the inventory of enslaved persons was projected at large scale on the hearth, and students read the names aloud to memorialize and honor them.

Even in its first iteration, several of the components that continue to make Woven Wind meaningful were present. The collaborative performance, outside of the classroom and the archive, required the decisions, voices, and participation of many different people, from the students selecting material to the community members who came to listen. The performance drew attention to the process of interpreting archival materials. It made the materials active, and part of a conversation. The projection and the sound of the names read aloud were ephemeral, and resisted any sense of completion. “Woven wind” could have served as a title even at this first effort, as well as for Vesna’s next interpretation of the materials, a radio broadcast of the names of the enslaved planned for March 2020. The onset of the pandemic prevented the broadcast.

Between October 2018 and December 2020 other voices and methods came to the project. Its focus turned emphatically to the living descendants of the enslaved, and to listening, learning, storytelling, and healing in the present.

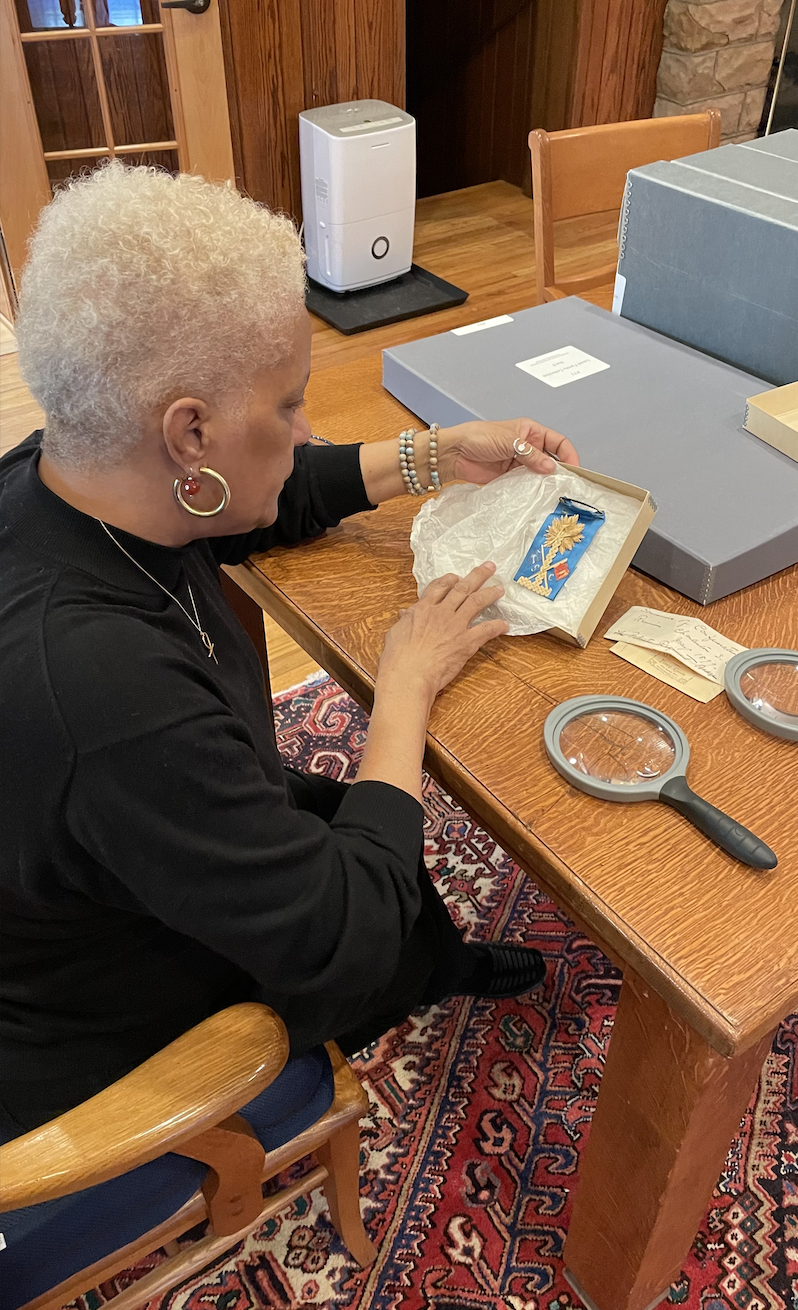

Nashville-based artists Courtney Adair Johnson, Marlos E’van, and Rod McGaha all joined the project as collaborators in 2020, bringing their perspectives on social practice, storytelling, and community engagement. Mélisande Short-Colomb, a founding member of the GU272 Advocacy Team, came to Woven Wind through the Roberson Project’s work with the Georgetown Memory Project (8). Mississippi civil rights veteran Jan Hillegas joined the project as a family history researcher, charged with tracing the living descendants of those enslaved by Quitman. With that research, the Woven Wind project connected with members of the Toles family, descendants of people who had labored at Monmouth, and found common purpose (9). Pauline Toles Allen had already been working to find her dispersed family members and to connect with them.

The Woven Wind collaborators and the Toles began to meet, build relationships and think about how they might work together—to find other members of the family, to consider the connections between people and place, to share stories. In December 2021, Vesna, Courtney, and Marlos joined members of the Toles family in Natchez and recorded oral histories at the Natchez Museum of African American History and Culture.

Those interviews in turn became the core of a workshop led by Méli, Woven Wind: Ethics of Memory, Oral Histories of the Toles Family, held at the McGruder Family Resource Center in Nashville on March 25, 2022. Participants listened and learned, and considered legacy, family histories, and the question of reparations. In July 2022, the Toles generously welcomed the artists of Woven Wind to their first family reunion in Natchez, and many more members of the family shared their stories with the project.

It was during the reunion that the project’s second metaphor was found. While walking around the grounds at Monmouth, Vesna and Méli were struck by the cypress knees emerging near the water. Vesna took pictures. The function of cypress knees is unclear (10). Anthropomorphized, and named after something they resemble, their name itself speaks to art, and to people that can’t quite be seen. For the project, cypress knees invoke the memories we want to honor, but which we cannot articulate, the stories we know are there, but that are not described in an archive.

The work of the project’s two metaphors—woven wind and cypress knees—has been combined in community clay workshops. Participants come together to listen to the Toles family interviews and think about family histories, to learn about the project and its critical archival work, and to make abstracted clay versions of cypress knees. Making the knees offers participants the opportunity to learn, to offer a contribution, to take small risks with an unfamiliar skill and new people, to remember together, and to know that the work of remembering can never be complete.

Once made, the ceramic cypress knees bear the marks and fingerprints of their making. They speak to the effort made to make them, but they do not pretend to speak for the past. They are opaque. Made by many people in shared moments and acts of learning, displayed and photographed together, they offer landscapes that speak to building community. The objects are impermanent, and their display temporary. Rather than carefully assembled and guarded like relics, the knees are left outside to dissolve on site, their making and unmaking modeling the ongoing memorial work of the present and future.

Thank you Toles Family for allowing us to listen and welcoming us to your family.

Woven Wind is supported by Tennessee Arts Commission Arts Access Grant, Vanderbilt University Scaling Success Grant, Mellon Partners for Humanities Education Collaboration Grant, Vanderbilt University, Engine for Art, Democracy, and Justice, Tennessee State University, Curb Center for Art, Enterprise and Public Policy Catalyst Grant, Current Art Fund, Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation at the University of the South, Sewanee, and Natchez Museum of African American Culture.

-

1. I would like to offer my heartfelt thanks to Pauline Toles Allen, Marlos E’van, Courtney Adair Johnson, Woody Register, Jan Hillegas, and Vesna Pavlović for speaking with me and for sharing their perspectives on the project.

2. Edward Baines describing Indian cloth in his History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain (London: H. Fisher, R. Fisher, and P. Jackson, 1835), 65-70, quoted in Sven Beckett, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), 8.

3. In conversation March 20, 2023.

4. Purple Sewanee, ed. Charlotte Gailor, Rose Duncan Lovell, Sarah Hodgson Torian, Lily Baker (Sewanee: Association for the Preservation of Tennessee Antiquities, Sewanee Chapter, 1932). The book was reprinted in 1961, in the wake of the university’s centennial celebrations and a fundraising campaign that forcefully reiterated the institution’s antebellum origins.

5. Lovell Family Collection, P71, Boxes 1 through 7. William R. Laurie University Archives and Special Collections, the University of the South. These boxes represent only the materials kept in Sewanee. Material related to John A. Quitman was donated to the State of Mississippi, and Joseph Grégoire de Roulhac Hamilton pulled other material for the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina.

6. My sincere thanks to Woody Register for pointing me towards this pamphlet and its characterization of the University of the South as a reliquary, and for the eye-opening description of Joseph Grégoire de Roulhac Hamilton and his work towards creating the Southern Historical Archives at UNC Chapel Hill.

7. The pamphlet, and the contents of the Lovell files, are fitting examples of the fact that archival materials, and the institutions in which they are held, are not neutral, but instead can be understood to constitute active and oppressive technologies. See for instance Ariella Aïsha Azoulay and her call to “unlearn” the archive in Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London: Verso, 2019). In her book Urgent Archives, Michelle Caswell advocates for community archives and “liberatory memory work” as a means of combating the white supremacy inherent in traditional archival systems. Michelle Caswell, Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge Studies in Archives, 2021). Caswell spoke to the Sewanee community on September 15, 2021 at the invitation of the Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation.

8. Richard Cellini spoke in Sewanee on September 23, 2019 about the Georgetown Memory Project, offering the talk "Slavery & the Old School Tie: Shouldering Responsibility for Alma Mater’s Role in the Slave Trade," at the invitation of the Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation.

9. Cynthia J. Parker writes about the Toles family and their connections to Monmouth in Monmouth: The Survival of a Grand Mansion Estate in Natchez, Mississippi, from the Era of Slavery to the Present (Master’s thesis, California State University, Northridge, 2010) 58.

10. See Christopher H. Briand, “Cypress Knees: An Enduring Enigma,” Arnoldia 60, no. 4, (December 1, 2021). https://arboretum.harvard.edu/stories/cypress-knees-an-enduring-enigma/.

TSU Hiram Van Gordon Installation

Woven Wind Hiram Van Gordon Gallery Opening and Performance

Courtesy of Lesa Dowdy

Project Journey

Galleries and Video Library